Chapter 3: School Days

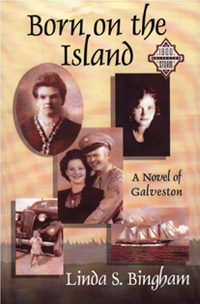

My father Milford Mack Glass served on the USS Long Island, a “baby flattop” converted from a cargo ship to ferry warplanes and troops from San Diego to Hawaii. That was as close to the sea as my land-locked Oklahoma family ever got. How my name came to be associated with Galveston I’ll save for a later chapter. For now, let’s consider the cover of the first edition of my novel Born on the Island, a collage of family photographs.

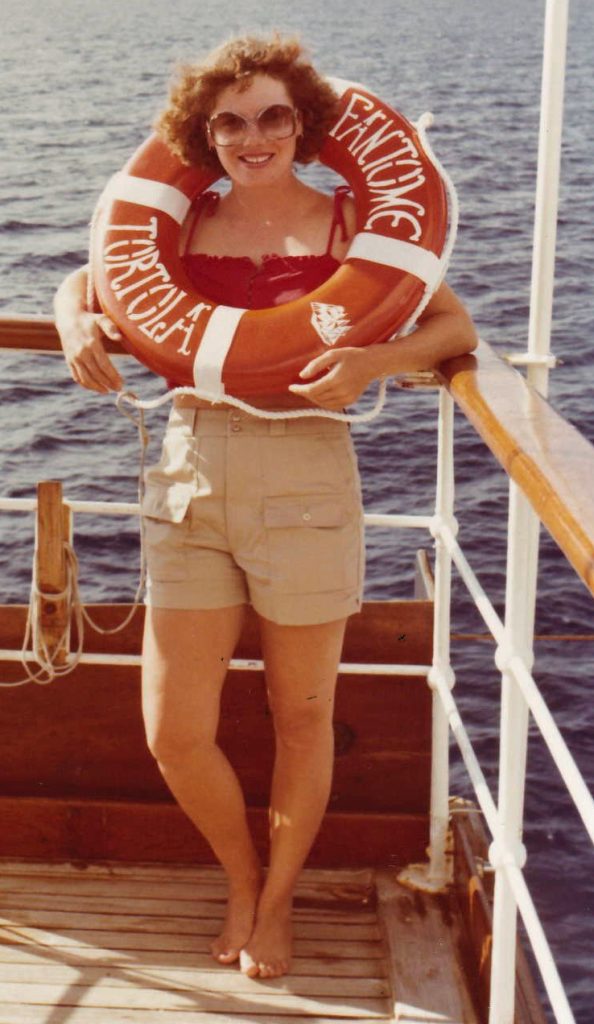

Uncle Herman, dressed in uniform and displaying his two-stripe chevron, has pride of place in the center. Aunt Clara’s silver cross can be seen at her throat. The couple suggest the era and circumstances of Emily and Harding Douglas, the star-crossed lovers in Born on the Island. From the same era is a photo upper right of the eldest Glass sister, Oma, whose death Daddy learned of when his ship was in port in Hawaii. My sister Betty looks a lot like her. The ship is the four-masted schooner Fantome I sailed on in the West Indies in 1980. And the toddler standing in front of Uncle Leonard’s car is me, Miami, Arizona, circa 1948. Family photographs suggest the era, not the wealth of the Galvestonians whose lives are the subject of BOI.

By the time I sailed on the Fantome she had already seen long and storied service as the Duke of Westminster’s yacht before passing through the hands of Irishman A.E. Guinness of stout fame and legendary ship-owner Aristotle Onassis. In her final incarnation, she was tricked out as a Spanish galleon and joined Michael Burke’s Windjammer fleet to ply Caribbean waters carrying one hundred “barefoot” paying passengers. We paid extra for a deck cabin but found it stifling and nightly joined the hoi polloi outside our door to sleep under the blazing stars.

Eighteen years later, with barefoot cruise a distant memory, my attention was caught one evening by a story on the evening news. The Fantome was in trouble.

On 24 October 1998, Fantome departed the harbor of Omoa in Honduras for a planned six-day cruise. Hurricane Mitch, then over 1,000 miles away in the Caribbean Sea, was expected to pose a risk to Jamaica and possibly the Yucatán Peninsula. Captain Guyan March decided to play it safe by heading for the Bay Islands and wait for the storm to pass.

By dawn on the following day, however, Mitch seemed to change course. Fantome immediately changed course for Belize City, where it disembarked all of her passengers and non-essential crew members. The schooner then departed Belize City, first heading north towards the Gulf of Mexico, in order to outrun the storm. Storm predictions proved extremely difficult, as the steering currents in Hurricane Mitch were very weak. When word reached Fantome that Mitch would most likely hit the Yucatán before she could get out of harm’s way, Captain March changed course for the south. It was too early to know that he was heading directly into the storm’s path.

The plan was to make for the lee side of the island of Roatan. In case Mitch made landfall in the Yucatán or Belize, by being on the southern side of the island, it would provide her with enough protection to hopefully keep it from getting damaged by large swells and high winds. However, Mitch, now a Category 5 hurricane with winds up to 180 mph, took a jog towards the south, directly towards Roatan.

As Mitch moved in on Roatan and Honduras, Fantome made one desperate attempt to flee to safety, now heading east towards the Caribbean. Mitch’s forward motion picked up, though, and Fantome was unable to outrun the storm. Around 4:30 P.M. on 27 October 1998, with Mitch having weakened but still at Category 5 intensity, Fantome reported that she was fighting 100-mile-per-hour winds in 40-foot seas. They were just 40 miles south of Mitch’s eyewall. Radio contact was lost with Fantome shortly after that.

On 2 November, a helicopter dispatched by the British destroyer HMS Sheffield discovered life rafts and vests, labeled “S/V Fantome,” off the eastern coast of Guanaja. It was all that was found of Fantome. All 31 crew members aboard perished and a memorial service was held for them on December 12, 1998.—Wikipedia

Daddy brought home souvenirs from the Pacific: a commemorative plaster-of-Paris lifesaver stenciled “USS Long Island,” a jar of miniature cowrie shells with which Betty and I constructed elaborate trails across the linoleum, a gray painted metal footlocker, an olive drab wool blanket, an album of grisly photos Daddy was ashamed of having bought showing grinning GI’s holding trophy heads of Japanese war dead.

Daddy didn’t have much to say about the war in the Pacific, only that he didn’t see much of it down in the bowels of the ship. He blamed the heat of the furnace he stoked for losing what had been a fine head of wavy red hair, his chief attraction for my mother. Uncle Herman came out of the service with even less hair and never went near a ship. Red hair runs in the family—our Irish gene.

My father dealt with mother’s bossiness the Gandhi way, with passive resistance. He thought I was too young to tell on him when he kissed Juanita Howard, a young woman in our church, but I did tell, and Daddy flung his knife at his dinner plate and broke it in half. Mother caught him in other sins, too. One night she left the house and returned with a pack of cigarettes she threw down on the table like a gauntlet, daring him to light up in front of his little children. Daddy pretended to savor his smoke but he learned what we all did, that Doris could trump any of your puny emotions. My parents were kids from the backwoods with hardly any education. Although Mother graduated from high school, she admitted she got by on her charm and spent the time filling her notebook with the lyrics to popular songs.

During the ten years my father worked in the copper mines, we moved from house to house, school to school, throughout the Globe-Miami area, several times back to the Federal Housing Project. There wasn’t a blade of grass for us to play on, nor any pretense that it was safe. Our front yard was the long dirt passage that ran between the barracks-like structures, shared with parked cars, barrels of kerosene lying in big wooden cradles—fuel for the cookstoves, and rows of sturdy clothesline. Childish imagination turned wooden clothespins into little people and the rag mop into a pony.

My parents must have felt particularly prosperous the Christmas of 1951, two days before my fifth birthday. Mother was bringing in a second salary and determined to make the holiday memorable. There was a tree in the living room, sitting up on the solid oak library table under which Betty and I played house. Mother said that Santa would come during the night and leave toys under the tree. That week we went to a Globe department store and I was asked if I could have any doll I wanted, which one would it be? Without hesitation, I pointed to the 18” Ideal Toy Company doll that promoted Toni Home Perms, a marketing tie-in meant to capture brand loyalty early in a girl’s life. Toni was endowed with extravagant blonde or red hair and she came with a miniature home perm set complete with tiny perm rods. We left the store without the doll and I thought that I had probably aimed too high.

We were always sent to bed early, so early that it was still light out in the summer. To pass the time, Betty and I invented games and told each other stories. We had a phrase Play like. That night I implored my sister to go to sleep or at least pretend to be asleep so that Santa could come. But there was something going on in the living room and we couldn’t settle down.

My mother was never content to simply let events unfold. She certainly wasn’t going to wait around for Christmas. The minute she was done wrapping the toys Daddy fetched from their hiding place next door, she got us up. And there she was, the gorgeous redheaded doll. Toni and I have celebrated nearly seventy birthdays together. One of us is beginning to show our age. From time to time I make her a new outfit and one year I sent her to a dollmaker to have her face repainted. Her sisters sell on eBay for about two hundred dollars.

*****

Daddy had a hard time buying jeans to fit and wore them deeply cuffed. Women didn’t have to iron denim and khaki pants but hung them on metal frames called stretchers. Mother washed clothes in a shared laundry facility equipped with zinc tubs and wringers. I loved the smell of the laundry, the products you don’t see today, bluing to make the whites whiter, Faultless Starch that had to be cooked. Mother dampened the dry laundry with a bottle corked with a sprinkler, rolled the pieces up, and kept them in the refrigerator. As she ironed, she pulled out one garment at a time. In Oklahoma she paid a Choctaw woman five cents apiece to iron our clothes.

Our unit was cool and dark, thanks to technology still used in the desert southwest today, an evaporative cooler that blocked the only living room window. A great finned drum rotated and pulled outside air through moist pads of wooden excelsior, giving the air the pleasant aroma of wet wood shavings. Daddy liked to nap directly under the cooler with his shirt off. Betty and I would set wave clamps in the clumps of chest hair which, perversely, was extra thick.

We were regulars at the Assembly of God Church of Claypool. One morning when Mother came to fetch me from Sunday school, Sister Blount called attention to the brooch Mother was wearing. She said it was vanity to wear such a thing in the house of the Lord and Mother meekly took the pin off and handed it over. I said, “Momma, why did you give Sister Blount your pin?” Mother said she had taken too much pride in that pin. Sometime later she saw Sister Blount wearing the pin and I learned a new word, “hypocrite.”

Daddy’s job ended at Copper Hills and he transferred to the Old Dominion mine in Globe, which today is a park and mining museum. For a while we continued living in Miami but drove over every Sunday to the big red brick Assembly of God in Globe. Children were sent to the basement for Sunday school and I learned about Jimmy and the atheist, told on flannel board. The atheist burns to death in a house fire and Jimmy, who could have saved the man, doesn’t lift a finger. I’m not sure what lessons children were meant to draw from the story, but for me the revelation was that you could not believe in God. Until then, I didn’t know such a thing was possible. Like a fish who has never been out of water, I had no concept of wet.

Local Apaches attended our church, depriving Daddy of the back row. Our drive took us through a section of the San Carlos Indian Reservation and Betty and I always craned our necks to see native women moving about the hillside in their wide skirts. Mother made all three of us squaw dresses with extravagant rows of rickrack, ornamentation a Pentecostal preacher’s wife couldn’t confiscate. Doris loved bling.

…your mom showed up in a station wagon with cousin Steve. She was wearing a short white dress and white go-go boots with her long black hair. She was so beautiful. For lack of better word: so hip! I couldn’t believe she was my mom’s sister. I look at pictures of her now, she still was movie star beautiful. I’m sure many heads turned in her direction.—Cousin Cathie Renard, 8/20/2020

Turquoise jewelry was as popular then as now in Arizona and we kids kept an eye out for blue rocks we could trade to a local jeweler for cookies. I could also get cookies out of Mrs. Nordak, whose arm and vocal cords were paralyzed. She would make some noise and I would say, “Yes, I do want a cookie.” We didn’t have cookies at our house. Mother strictly rationed our sugar intake and taught us early to take care of our teeth. Betty and I still rush from the table to brush.

One of the houses we lived in was at the top of a steep hill. Aunt Helen and her quilting bee set up their frame in the empty house next door and while women stitched in the living room, little girls went exploring. An older child invited me to climb into the old refrigerator, another hazard children used to die from. Fortunately, someone discovered me in time.

That was the house we lived in when my sister was born, where, overnight, I ceased to be the center of attention. Hearing them coo over her baby bed enraged me and I reached through the bars and yanked the bottle out of her mouth. That would show them who was cute! When winter came, Mother moved the crib to the kitchen where it was warmer. One day while she was distracted, I replaced the baby bottle with the pepper sauce that always sat on the table next to the salt and pepper. There was a hole in the top of that bottle, too, and I’m not sure I meant harm. It might have been a scientific experiment. The baby’s screams brought Mother running and she telephoned the doctor to find out what to do. A nurse told her to give me a dose of my own medicine and Mother threw me across her lap and shook pepper sauce down my throat. Now she had two screaming children.

When Betty got big enough to play with, I climbed the shelves of the big closet in the hall and handed down the box of lye and the spoon Mother used to dip it out, a laundry product and another household hazard. Betty spilled the lye on her legs and started screaming. This time a more experienced mom didn’t call the evil nurse.

At church, my parents were friends with Paul Cunningham, a handsome young pilot back from the war and ready to settle down. He asked my daddy if there were any more like Doris back on the farm and it so happened that her sister Helen was passing through after visiting their older sister Audrey in California. Paul and Helen hit it off at once and he proposed. She stalled. One day he took her for a drive in the desert and said, “Are you going to say no and make me miserable for the rest of my life?” Aunt Helen said, “I’m going to make you miserable for the rest of your life and say yes.” Their older two children Stevie and April were born at Miami-Inspiration Hospital, same as me and Betty. Daddy said we cost $25 apiece.

Mother owned a Kodak box camera and on Sundays when we came home from church, she liked to snap our picture against a backdrop of the tailings. One Sunday we got out of our dresses before she remembered to get a picture. There we are, hand in hand, our curls coming undone, dressed in white panties, socks, and shoes. I’m wearing a tiny strand of pearls.

Mother was superstitious and put as much faith in astrology as she did in religion. She believed in dreams and angels and often heard voices. When faced with alternatives, she would open the Bible and have one of us point to a random scripture that would hold her answer. We knew that I was a Capricorn and Betty a Virgo. Mother was a Leo and not compatible with Daddy’s Sagittarius.

The angels took me up on a high mountain. It seemed like the very top of the world. They took a big hunk of earth clay like and laid it on a conveyor belt. I could see everything that went on and I suddenly realized I was inside that piece of clay and was being formed into a beautiful woman by all of God’s little workers. I knew Jesus was in complete control and was giving the orders. He had divine Kindness yet complete authority over it. As I moved down the conveyor belt I was being molded and could feel every feature of my body being formed even to the forming of my eyelashes, eyebrows, arms, hands, fingers, toes, every hair was put in my head. Jesus was directing the forming of me. I was inside but I was not yet a living soul, couldn’t breathe. I felt my inward parts being formed and my face, the nose, lips, eyes. I think the very last thing he formed was my reproductive system and I was about to the end of the conveyor belt actually a long table. At the end on that high hill I looked out into space. Millions of miles of space and I saw it coming—a beam of light like a laser beam and it pierced that clay body and I started breathing and stood upright. I was perfect in beauty, oh so beautiful and so perfect. Then all of a sudden I was back in my chair and I looked into a mirror and I didn’t look that way, so he must have been showing me my new body I’ll have in heaven. [Doris Niehaus, January 1985, handwritten account of psychosis after Orkin termite spraying]

When Daddy worked graveyard shift, we sometimes took him supper. Mother would drive the car right inside the big steel structure where the hoist shack was located and make us a bed in the backseat. High up under the rafters, bats darted through the lights feeding on insects. We were on a mountainside eye level with the City of Globe’s water supply. One night Daddy led us over a catwalk and opened a hatch to show us the water, playing his flashlight across the dark surface and giving me a new motif for my nightmares.

We moved so often that sometimes at the end of the school day I didn’t know where home was. On one such occasion, a teacher drove me through the neighborhood until I spotted something that looked familiar. The teacher told our class to be sure to tell our parents there would be no school on Tuesday. On Tuesday, Mother dropped me off as usual and I sat on the steps all alone wondering where everybody was. A woman working in her yard came over and said, “Didn’t you know there was no school on Tuesday?”

My progress through the elementary school curriculum was so haphazard that I missed foundational skills such as days of the week, cursive writing, and multiplication. My fourth-grade teacher sent home flash cards and my little sister drilled me in the times tables. I still can’t add, but I know my multiplication. Betty loved knowing the answers, which were printed on the back. Usually, I was the teacher. I wanted my sister to know everything I knew. For a long time she couldn’t make a “y” sound and said “less” for “yes.” I had to work on her to correct that. When school let out for the summer, I set up a classroom and assigned her the empty pages of my language skills workbook. Years later I would Xerox college notes and mail them to her. Betty missed out on high school but got a GED, then went on to college and majored in English literature. I’m never satisfied with a piece of writing until my sister has read it.

Mother considered us part of herself and told us everything. We never ratted on her. Sometimes there were secrets she tried later to make us forget, such as where babies came from and that there was no Santa Claus. We were witness and accomplice to her love affair with Richard McLendon, the manager of her Safeway, and Joe Unomuno who took us along on their date to a drive-in movie. It was the first movie we ever saw, the first junk food we were ever allowed.

Stupidly brave, Joe Unomuno showed up at our house one night when Betty and I were home alone. We didn’t know any better than to open the door to two foreign men. Joe had brought us candy and translated for his friend who said that if we planted the candy, we would get more candy corn. In geography class the next day, I bragged to my teacher that I knew someone from “Bosco Country” and she said there was no such place. She was wrong. Joe Unomuno was a Basque.

Even when Mother was looking after us, we weren’t necessarily safer. When she worked in the coffee shop at Copper Hills Motel, we stopped by one day to see her friend and fellow waitress. The women had some serious dirt to dish and Mother sent us off to play with a warning don’t get dirty. My sister, not yet in school, did get dirty and thought it would be prudent to rinse her socks in the deep end of the motel swimming pool.

I don’t remember seeing my sister tumble in, but I was instantly drawn to the edge of the pool where I saw her looking up at me, hair fanning out around her face. She rose slowly towards me but didn’t come close enough for me to grab her. A child drowns in complete silence. An adult sunning himself on the opposite side of the pool never looked up. She went down and again slowly rose towards me, this time with her arms above her head. I was flat on my stomach, arms plunged in the water. Our hands connected and I hauled her out of the water. I was eight years old and had just saved my sister’s life.

Choking and terrified, we ran to the car to tell Mother what happened. It was the first instance I remember of my mother’s marvelous ability to deny the truth, in this case that she had almost let one of her children die.

*****

It took sixteen hours of hard driving to reach the southeast corner of Oklahoma, pausing only for gas and the occasional nap. Mother would pull off the road and cover her eyes with a rag while we kept a nervous eye on the traffic, ready to wake her if anybody stopped. One time the car broke down in the desert and a gallant long-distance trucker took out the busted fuel pump and drove to the next town to look for a parts store. Mother prayed that he was a good man and wouldn’t leave us stranded. As the sun began to set, it got cold and the Arizona highway patrol came along and let us sit in his car. The trucker returned with the new part and installed it. He refused the money Mother offered but accepted the Bulova wristwatch we were taking to Grandpa.

It was always dark when we crossed the Pushmataha County line. One time, as we neared our destination, Mother rolled down the window and cried, “Smell that good Oklahoma air!” from which came the title of the novel based on our lives. Doris didn’t recognize her fictionalized self. “Now which one is you?” she asked. “And which one is Lezlie? And who’s that awful old Reen?” Irene is the character based on Mother.

*****

Mother let me subscribe to a weekly teen newspaper called Grit, the only periodical in our house other than the Antlers American. Books were textbooks, so precious that school children spent the first day of the new term protecting them with special brown paper printed with local advertising, Berry Drug, Roy Jackson Motor Company, Finley Feed and Seed, Farmer’s Exchange Bank, folding the heavy paper exactly to fit, creating a flap, slipping in the covers, closing the book to note with satisfaction how taut and neat the job. I remember my excitement every year at being given a fat new anthology of fiction. The teacher didn’t like it when we read ahead and I learned not to give away plots.

In junior high, an hour of our schedule was “study hall” when we were supposed to sit quietly in the auditorium doing our homework. A former cloakroom had been converted into a makeshift library where we could check out a book by leaning across a half-door and pointing out the book we wanted. You could only judge a book from its cover, its spine actually. A young library assistant would fetch down the book for you. You got a new book by turning in the one you had finished. I read my way through Betty Cavanna, Nancy Drew, the Hardy Boys, and a series set in the world of sulky racing. I couldn’t fathom what a sulky rig might look like. I went through a long fascination with science fiction before turning to mysteries.

In 1959 after Grandpa Perry’s stroke, the only Perry daughter living in Antlers, Hermione Berry, sold the farm and moved her parents and brother to a roomy house on Standpipe Hill adjacent to where the new high school stands today. Living in town, Uncle Bud had to make new habits, which couldn’t have been easy for him. On the farm he had chores, but now there was nothing to fill his days and he began to walk, explore, and look for people to talk to.

At the city dump he scoured the mounds for useful items to bring home. He maintained great balls of twine, aluminum foil, and rubber bands, recycling long before it was fashionable. Downtown, he kept an eye out for anyone inclined to tarry. George Alva Perry, Jr. couldn’t look you in the eye yet he somehow managed to buttonhole complete strangers and get them to listen to his monologue, noting first the deaths of his parents, moving on to his phenomenal record of church attendance, and then reciting statistics about gopher trapping.

Backpacks hadn’t come into fashion, but Uncle Bud modified lady purses and other commodious bags with straps and slings. Aunt Hermione and later my mother tried to keep him presentable, but their efforts were mostly wasted except on Sunday when Uncle Bud took his shower and let someone shave him for church. His record of consecutive Sundays got to be some very large number. He would’ve seen pastors come and go, babies grow up and start families of their own. I’m glad that the nursing home where my uncle finished his days was just across the street from his church.

As useful and handy as Uncle Bud had been on the farm, he had never prepared meals for himself and seemed to have no idea how to do it. Aunt Hermione had her own family to tend to, as well as helping out at Uncle Wilburn’s drugstore. She solved the problem of feeding her brother by dropping off TV dinners for him to heat in the oven. Adhering to his usual frugality, Uncle Bud ate half a dinner and saved the rest for his supper.

My mother was working for Dr. Hawks and too distracted by her new business career to notice how thin Uncle Bud was getting, but one day she saw that he had punched extra holes in his belt to keep his pants up and vowed that we would move in and fatten him up. Or maybe she was just tired of living in the back of Thomas’s clinic. Uncle Bud qualified for government surplus commodities and the pantry was stocked with plain-labeled tins of beef, powdered milk, peanut butter, American cheese. Uncle Bud started every meal saying grace and finished with peanut butter and crackers.

We were an odd little family, Dr. Hawks and Doris, two pre-teen girls, and my gopher-trapping uncle. The Kiamichi Wilderness began just across the street from Uncle Bud’s house. Older kids parked there to make out and drink beer. Betty and I explored its trails, discovered a cold clear spring, and drank the water to see if it would kill us. We waded in a flooded gravel pit. One time, with Betty clinging behind me, I wrecked my bike on the long gravel descent into town and we limped home crying and consoling one another. I suffered a bruised coccyx that made sitting a misery and Mother took me to the new chiropractor in town for an adjustment. Nelson Conrad, the doctor’s son, six feet tall, acned and crew-cut, was a sort of boyfriend although we were too shy to speak to one another.

Thomas Hawks, an Aries, had a quirky personality that tended either to amuse people or infuriate them. Margie Mills was working in her kitchen one day when she heard someone come in the front door. After a while she left what she was doing to go see who it was and found Dr. Hawks coming out of the bathroom drying his hair. He needed a shower, he explained. Margie, a former telephone operator who knew how to spread a story, confirmed Thomas’s reputation for eccentricity.

From time to time, Thomas showed up with some farm animal given in trade for a pair of glasses. Once it was a black goat he brought home in the backseat of the car. We named the goat Billy and treated him like a pet until the day he joined the contents of the freezer. Betty and I bottle-fed a pair of calves. We raised baby turkeys, Turk and Dirk, who mysteriously disappeared one day while Uncle Bud was home alone. My calf turned out to be a heifer who made the move to the country when we bought a house of our own. Heifer grew to milk cow and it fell to my more tender-hearted sister to get up in the freezing dawn to relieve pent-up udders.

Aunt Ruby’s husband, Max Harrell, was visiting from California and announced his intention to fish the Kiamichi. Uncle Bud was hoping somebody would ask for the fishing worms he had been saving. In town there were fewer gopher trapping opportunities and he had gotten interested in raising gourds and amassing statistics about their size and weight. As he came across earthworms, he carefully transferred them to an old slop jar buried between the cellar and the outdoor brick oven where we burned our trash. Occasionally he threw in a few table scraps to feed them.

We stood by while Uncle Bud attacked the long-buried pail with a shovel. Probably be ten thousand worms in there by now, Uncle Max speculated. When the pail was loosened all around, Uncle Bud gave the handle a mighty yank and up came a rusted rim. Not one worm, not even a pail.

Mother went to Huntsville, Alabama to train as an optical technician and Dr. Hawks bought equipment to set up a lab in the big empty space behind the clinic. Mother was fast and dexterous with her hands, good at dealing with the public, something Thomas emphatically was not. Mother cleaned and organized his office, kept the doors open for regular business hours, and thanks to her industry, made them prosperous enough to buy a house and seven acres east of town. Long before same-day optical service was available in big cities, you could leave Hawks Optical wearing your new glasses.

My contribution to this family enterprise was filing the new lens stock that came in the mail. Lenses start out the same size. Mother would mark the focal point and trace the pattern of the selected frame with a felt-tip pen, then etch the shape with a glass cutter, and roughly shape the lens by clipping away the excess. Next, she would bolt the lens in place against the first of several grinding stones, secure the pattern against a separate cam, and the grinding stone would echo the shape of the pattern. A finer-grained stone polished the edges. I still remember the screech of a lens making the turn against the stone as a thin jet of water spattered against the wheel cooling and lubricating. A hot salt pan was a permanent fixture on our kitchen counter, a tray of tiny glass beads Mother plunged plastic frames in to make them pliable enough to mold to a patient’s face.

Occasionally a frame would snap in two or a lens would not break along the etched pattern and Mother would cry God bless America! Pentecostals do not use the Lord’s name in vain. Mother asked the preacher to rid her of this dreadful habit but his prayers were only partially successful. Betty and I were not allowed to say “gosh” or “darn,” obvious substitutes for “god” and “damn.” In college I set out to learn to swear without blushing.

Thomas Hawks made fun of Mother’s superstition and old-time religion. Unlike her first husband, this husband was too lazy or indifferent to fight with her, and perhaps because he was untamable, he became an object of fascination and remained so his entire life. Thomas was one of the few educated adults I knew other than my teachers. While I had no love for him, I didn’t loathe him the way my sister did. We were separated a lot during our teens and I didn’t see as much of his sadistic side. My beatings came from Mother who was determined not to let me grow up.

The Class of ’64, the first post-war generation to come of age, was funneled into area colleges as a matter of course. Somehow, I expected to be one of them, even though there was no preparation in my family, no writing off for brochures, no campus visits, no discussion of how we would pay for it. Thomas was the only family who even broached the subject of higher education to me. “You’re smart enough to be an optometrist,” he said to me one day. “Take all the math you can get.” That was the extent of parental advice as well as a statement of his self-worth.

My mother resented the schools’ quasi-governmental authority over us and when it suited her to flout that authority, she did so, taking us out of school no matter where we were in the school term or how it set us back, what essential learning we missed, or in my sister’s case, robbing her of her high school years. Mother cajoled the kindergarten in Claypool into taking me, even though I wouldn’t be five till December. She had gotten a job and was frantic to find childcare. In junior high, she wrote a note to Mr. Jones saying that I had been diagnosed with TB as a child and needed to be excused from 5th period PE to come home and rest. Instead, I walked up Standpipe Hill to start supper for my family.

It’s ironic that Mother, who imperiled my life over and over, fretted about my health. Having started life in an incubator, I tested positive for TB in grade school, the “patch” test that raises a bump on your arm if you’ve developed an antigen to the bacillus. A positive response does not indicate an active case of the disease but does mean you will get your chest X-rayed yearly. In Oklahoma, Mother took me up in the Kiamichi mountains to a hospital dedicated to the treatment of TB.

Eastern Oklahoma Tuberculosis Sanatorium was opened for the admission of patients on November 1, 1921, with facilities for caring for about 50 patients. This sanatorium is located on the Winding Stair Mountain about three miles west and a little north of the town of Talihina. It is located on a ledge of mountains overlooking a broad expanse of the Kiamichi Valley. The hospital is about 800 feet above the valley.—Minnie Wagoner, History of Eastern Oklahoma Tuberculosis Sanatorium, August 7, 1973

Mother worried that my heart beat too fast, faster than hers, 120 times per minute, typical for a child. She worried that I didn’t get enough calories and was always scheming to make me eat more. She gained leverage as my social life blossomed. “Two more bites and you can go to Becky’s house.” “Drink an egg malt before you go to the game.” (Raw egg, milk, sugar, blend till foamy.)

I would’ve eaten more if Mother had been a good cook. I liked Grandma’s cooking and Aunt Ruth’s, in fact, almost anybody’s cooking but Mother’s. Even when she owned a stove, Doris tended to cook one dish meals in an electric skillet. Growing up, a bowl of cold cereal for breakfast would have been a treat, but Mother made us eat protein. She had a special talent for ruining eggs.

In her defense, she was a working mother before fast food had been invented. She dreamed up labor-saving schemes such as cooking a month’s worth of spaghetti and freezing it in plastic bags. Or throwing all the leftovers in the blender and calling it soup. She came home from visiting cousin Perry in California with ideas about mega-vitamins and nutritional supplements. She bought a powerful blender and pureed raw beef liver with tomato juice and drank it. She pulverized handfuls of vitamins and supplements and drank them, too. And who’s to say it didn’t work? She lived a lot longer than any of us thought she would, dying a day shy of her 82nd birthday.

The house east of Antlers was the first my mother ever owned, but by no means the last. Thomas pictured himself as a country squire and had a large stock tank built at the back of the property to water our one cow, the only evidence today that we ever lived there. Betty and I were eager to swim in this body of water but were discouraged by the S-shapes of water moccasins. Thomas stocked the pond with catfish and used to go down and toss in cattle feed till he lost interest.

My mother almost immediately set out to improve the property. Unusual in that part of the world, our house had an attached garage. Our neighbor Mr. White was a stone mason whom Mother hired to turn the garage into a den with a red brick fireplace flanked by built-in bookshelves. Not that we owned any books. Mother displayed her fancy glassware, a rare and unexpected gift from Mrs. Anderson, my grandmother.

As men came and went in my mother’s life, she utilized their various carpentry and plumbing skills. It was always easier to add a new room at the end of the house where there was already one of the four walls. The house grew wider and wider, became two houses joined end to end, with two full kitchens. Betty and I kept the bedrooms in the old part of the house while Mother moved further and further away, claiming each new room as it was completed.

With a house perpetually under construction, building materials were stacked and waiting in the front yard. Sometimes doors were missing or there was no functioning kitchen. One of Mother’s specialties was taking out walls and installing 8’ sliding glass doors. The door in Betty’s bedroom slid open to a sheer 4’ drop through which my daughter’s stroller once flew, barely missing killing her. When Mother left Antlers, she sold the house and carried the note at 8%. The buyers were honest folks who made payments even after the house was struck by lightning and burned to the ground.

*****

Growing up, fiction occupied and distracted me from a homelife that was often chaotic and scary. As a preteen, my own stories began crowding out other people’s. I didn’t yet write my stories down, I just thought them, and that was dangerous enough. Our church taught that Jesus could hear your thoughts, in fact, He knew what you were thinking even before you thought it. This doctrine so disturbed me that I set out to disprove it, risking my immortal soul. I may have looked like an innocent fifth grader, but on the inside I was a blasphemer. I don’t believe in you, Jesus, I chanted over and over in the privacy of my own head. When, after a few days repeating this mantra and I was still breathing, I knew I had proven that my thoughts were not being monitored.

Living with a dangerous and unpredictable mother might have trained me to maintain an innocent façade but when I published my first book, my thoughts became public and some readers objected. While I haven’t provoked death threats like Salman Rushdie, I have been called out by a few outraged females. One stood up at a reading and denounced me for sullying the glorious history of Galveston by including a lesbian character. Another disrupted a women’s club meeting to object to Billy Porterfield’s blurb that Galveston innkeepers should replace the Gideon Bible with Born on the Island.

One can overlook the criticism of strangers, but when one’s family is offended, it’s another matter. Daddy’s copy of my first book passed from hand to hand among my Nocona relatives. Cousin Betty Gail reported that after Aunt Betty read it, she said, “You’d think she could have waited till Mack was dead.”