Humans once argued about how many angels could dance on the head of a pin. Once we wore ourselves out on that one, we moved on to the larger question of just where we fit into the scheme of things. Were we God’s crowning achievement, a lower form of angels, perhaps, or just another animal that evolved on planet Earth?

As we know, that latter question was settled by Charles Darwin, who worked out that we’re not divine at all, merely the smarter cousin of apes. People are still muttering about this. Having assumed our place in the natural order, we made a case for our specialness. Every creature has an attribute that helps it capture prey and stay one step ahead of its predators. What was our special or unique gift? Could we define “human” in a way that put us in our own special class of animal?

When I was in school a hundred years ago, the yardstick that defined humanness was whether or not one used tools. Personally, I have never used tools, but a lot of people (men mostly) thought that tool use defined us as a species. Then somebody, I forget just who, filmed wild chimps purposely shaping sticks to pull ants out of mounds, and we were forced to concede that tool-use was possibly not the exclusive bailiwick of humans.

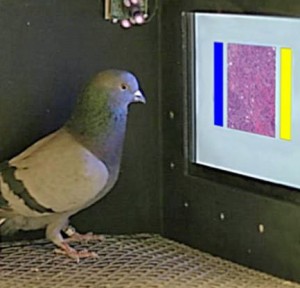

As we formulated new definitions for what it means to be human, one wily creature after another squeaked past the goal posts. And since those early days of nature photography, PBS has served up a steady and humbling diet of proof that animals do all sorts of things we thought only humans could do. They devise and use tools, communicate with one another, solve puzzles involving a series of logical steps, recognize themselves in mirrors, create art, speak to us with sign language, even operate computers if you make it worth their while. Yes, and animals ride bicycles, star in their own TV series, and make you laugh on YouTube. Newsflash: Pigeons read mammograms! [ http://www.newsweek.com/researchers-train-pigeon-pathologists-read-mammograms-396534 ] There goes another darn definition!

So, is there anything that delineates us from the apes, exempts us from the ignominy of taxonomy? I say yes! Two things, actually. We humans amass stuff and we go to extremes.

While not freeing us from the animal kingdom, the fact that we amass stuff explains how we’ve been able to leap-frog forward in evolutionary terms while other creatures have hardly changed at all from years and years ago.

Before you point out that sea polyps amass coral reefs big enough to be seen from space, and beavers amass, pack rats amass, even ants amass stuff, they don’t do it on a scale to place them among the firmament of angels. We dig up humongous amounts of dirt, from which we extract, refine, concentrate, distill, frack, purify, plenty enough to distinguish us from any species, especially apes, who won’t even bother to keep up with their sharpened sticks. But I’m not talking about the material we dig up from the earth. I’m talking about information. We humans amass information, and we go to extremes doing it. In fact, new words had to be invented to describe these extremes, words like “terabyte.”

Allow me to sketch a brief and painless history of how our preoccupation with amassing information came about. Early humans figured out a way to pass along to the next generation the hard-won knowledge of their tribe. They did this by inventing writing. Using their sharpened sticks to scratch out a shape in dried mud, they declared that this symbol stood for “saber-toothed tiger.” It was only a matter of time before we had word processors and texting. After that came sexting, of course, but we’ll talk about that another time.

Prior to writing, humans had to carry around everything they knew in their heads. Their kids had to spend their childhoods memorizing this stuff so they could carry it around in their heads and pass it on to their children. Youngsters today will hardly know what I mean by “memorizing,” because today we don’t even have to remember phone numbers. But it turned out that having to remember stuff was good for “early man” because it focused human evolutionary development on the brain. Rather than becoming faster or stronger, or able to digest woody fibers, we got smarter and smarter. Your 21st century model human being can think circles around dumb beasts such as cats and dogs, who didn’t even develop a sense of humor.

And for a long time the oral tradition served us well. But memorizing has its limitations. You dare not stray far from the known. Get it wrong, and you risk becoming somebody’s next meal. We know from digging up places that many ancient civilizations died out because they kept doing the same thing over and over, one generation repeating exactly what the previous one did, until eventually something came along that demanded a response their father had not made them memorize. Say, the planet got a few degrees warmer.

Writing allowed us to set down on paper things that future humans didn’t have to learn through trial and error. Children, no longer bound by only as much as their father could remember (my father could remember hundreds of bad jokes), were ahead of the game. Starting out on the level above the one achieved by the last generation turbocharged evolution for our species and led to the creation of a shared brain, the Internet.

Nowadays we don’t have to remember the past. You can Google it. Nor do we have to know much, especially if we’re a GOP presidential candidate. Yet even as 7.2 billion of us cover the earth, the individual has never had more power. Consider how a single alienated young man can find others like himself online and plan mass murder.

Reading history makes it clear that civilizations that carried their peculiar fixations to extremes, whether piling rocks on top of one another, or cutting down every tree on the island to grease the skids of a stone god, led to a bad end. Extremism is the place you end up when you push the envelope too far. (I feel a cross-stitched sampler coming on.)

But I’m not sure we have any choice in the matter. It may be what makes us human. Going to extremes is a by-product of specialization. Here is “scientific proof” of my thesis:

- Young athletes striving to eke out a nanosecond (another new word!) over the previous record has led to spectacular achievement in sports, but also to extreme sports. Does it improve our chances of survival as a species that some of us jump off mountains wearing little more than a baggy windbreaker?

- Today’s “reality” shows had their genesis in Ted Mack’s Original Amateur Hour. I think you’ll agree programming is edging toward the extreme if you check out the latest episode of America’s Got Talent.

- Snack chips used to come as either potato or corn. Now Frito-Lay’s website guides you through 115 varieties. I think it’s very telling that one section is labeled “extreme flavors.” We can only hope this trend leads to extinction! And soon, while I can still get into my pants.

- In the world of fashion, beautiful women once glided along the runway modeling the latest haute couture designs. Coco and Yves are dead. This year’s Paris Fashion Week presented a dystopian version of itself, skeletal creatures stalking the catwalk, outfitted in styles that made headlines, not because of their beauty, but their weirdness. When human beings can no longer figure out which is front and which is back, extinction can’t be far behind.

- In fine arts, Leonardo was concerned with depicting, as faithfully and beautifully as possible, the human body as light played over its planes and surfaces. Cameras came along and took over his job. Artists, being creative sorts, took Art in a new direction, making things that even today cause gallery visitors to exclaim: “I could do that!”

- Early novels were equally wedded to reality, but readers today needn’t confine themselves to the merely possible. Fantasy, sci-fi, mystery, romance, and dozens of other genres offer a specialized reading experience. Some critics think that novels committed suicide by pushing the envelope to extremism.

- With the death of the Really Good Novel, novelists themselves took off for Hollywood and began writing fiction for the movies. That art form, too, is beginning to give off the tell-tale light of pre-extinction brilliance.

You can probably think of your own examples of things that started life as revolutionary, beautiful, useful, or transformative. And you can recall the trajectory of its history as it changed beyond all recognition in subsequent “improved” versions.

We speak of the evolution of information technology as if the wires and tubes that constitute the Internet took over the function of evolving in our stead. Adam passes the baton to atom. We dimly understand that increased computing power has shortened the computer’s evolutionary cycle and that things they are a’changing very fast indeed. We wonder if humans are even in charge any more. We’re carried along by our devices, helpless without them. Wisps of nostalgia waft in the air, as if we didn’t quite get enough of something before it went away, vinyl records, a movie shot in black and white, bell-bottomed pants.

Writing brought us to the digital age. And as we are wont to do, we amass information with the same obsession that Egyptians once mummified cats and the Chinese fired clay warriors. Progress was slow at first, but now next generations come along so fast your neck snaps.

Perfection is not a plateau; it’s a slope. You have no way of knowing when you’re there, or if one more step will take you over a cliff into oblivion. If digging up stuff has taught us anything, it’s that animals that got too specialized for their britches ended up in trouble. Put too much vital energy into big horns, beaks, or eating one kind of food, you might not be around to teach the next generation about saber-toothed tigers.