A Memoir

Linda S. Bingham

Sometimes, to know where you are, you have to look at where you’ve been.

Chapter Two:

Throughout their eleven years of marriage, my mother took us out of school so often that I didn’t finish in the same school I started until the 8th grade. When Mother finally did get a job in Antlers, it was keeping office for an optometrist named Thomas Hawks whose clinic was in an old red brick building on Main Street. Mother had left her Singer in Arizona and Grandma helped her sew a new professional wardrobe by hand, observing that Mother’s stitches were finer than her own.

The last home we lived in as a family in Arizona was a 55-foot Great Lakes mobile home that was brand-new and came with modern features such as a glass-fronted washing machine and propane cooking stove. Our first TV may have been part of the furnishings. When the marriage broke up, my parents divided the property as well as the children. I stayed in Arizona with Daddy and the Great Lakes. Betty and the Buick went to Oklahoma with Mother.

The Great Lakes, being mobile, relocated to Antlers a year or so later when I was in the 5th grade, then went back again as far as Lubbock where it sat in Uncle Troy’s backyard until repossessed. I remember spending Christmas with Daddy at Troy and Hazel’s old house, sharing a bed with my cousin Kathleen, while Daddy slept in a storage shed out back. I wondered why he didn’t sleep in the Great Lakes and he said he was afraid the repo man would haul him off.

Without Mother around to boss us, Daddy let me stay up past 9 o’clock and watch the TV mother had metered so stingily. Daddy got down his carton of Winstons from their hiding place and smoked whenever he felt like it. I was shocked but got used to it. Although Daddy didn’t make me go to church, when Easter arrived, I got a new pink ruffled dress and hid Easter eggs with my younger cousin Mary Elizabeth. Her dad, Uncle Tommy, was an amateur photographer who developed prints in big pans of chemical set out on the kitchen counter. He snapped our photo showing off the decorated eggs. Mary Elizabeth’s mother Gladys had put my hair in ringlets.

Mother was too impatient to let us have long hair. She was forever whacking at our hair or giving us home perms. One day Betty and I arrived at school with fresh smelly perms and when a kid wrinkled his nose and said “P-U,” I went home and stuck my head under the faucet and washed mine out. You were supposed to let the ammonia “set.” Betty was too afraid of Mother to wash hers out and in photos of the era, she’s the one with the poodle perm.

Daddy didn’t know how to give perms or put a little girl’s hair in ringlets, so he utilized a skill he learned in the Navy, braiding. I complained about wearing dresses and he bought me blue jeans and ironed them when he ironed his own, with knife-crease pleats. When Daddy worked graveyard, my cousin Gladys picked me up after school and took me to their house in Globe. I inherited my Dad’s deadpan humor. One day Gladys arrived early to pick me up from school and while she waited, tidied the car, dumping the dashboard ashtray out the window. Seeing the huge pile of butts on the ground, I said, “Been here long?”

When the school term ended, I rejoined Mother and Betty in Antlers. The Great Lakes moved, too. Betty remembers making the perilous trip over the mountains of New Mexico with the man Mother hired to haul the long, long trailer. Mother rented a space to park it next to a little creek that ran behind the Antlers Inn. We named the creek Our Miss Brooks after the TV show.

New families didn’t move to Antlers very often, but that year Brantley School enrolled five out-of-state girls, the Glass girls and the Shaws from Dearborn, Michigan. Fred and Vi ran a grocery store on High Street. Our blue and silver trailer was parked midway between Shaw’s Grocery and the house they rented at the top of High Street. In addition to the three sisters, there was an older brother George, their Nana, and a dachshund named Dutch. Cindy and I were in fifth grade, Betty and Maria in third, and Sarah in first. We all thought the Michigan girls talked funny and we kept asking Maria to recite “Little bitty spider climbed up the wooter spout.”

Knowing how acrimonious things were between our parents, they probably feuded over who would make the payments on the Great Lakes. Mother found us a cheaper place to live, the rear of the building where Dr. Hawks had his clinic. He had been living there in bachelor squalor after his divorce from a Filipino woman named Mary O’Brien Hawks, with whom he had a son. Mother made it a home, hanging up sheets and quilts as room dividers. From my bed I could see a large opening under the eaves in the back wall where an attic fan had once been. One night I could see snow blowing through that opening as I huddled under my electric blanket.

There was a toilet and a sink at the back of the drafty old building and we took showers in Mr. Denney’s abstract office next door. One night, crowded into the tiny bathroom waiting my turn for the shower, I burned my leg on the metal stove. Childhood hazards abounded in our world. Mother cooked in an electric skillet and heated water and washed the dishes in the same pan. The lack of a kitchen never bothered Doris. In fact, she usually turned her kitchens into a lab to make glasses. At school one of the kids taunted that my mother was shacked up with Dr. Hawks.

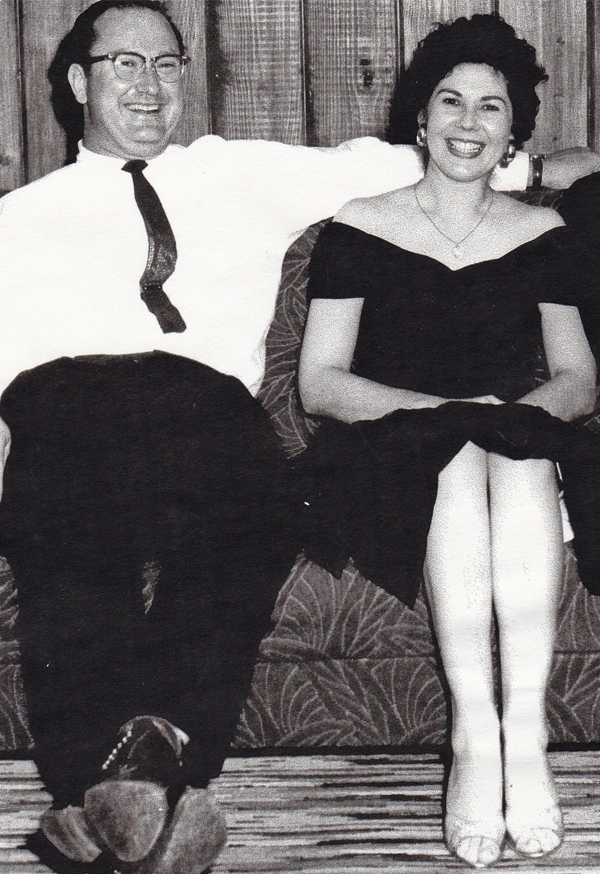

Thomas had been a bad drunk before Mother took him over and saved his business and possibly his life. A photo taken the day they got married shows Doris sitting between Dr. Hawks and his friend Red. Everybody is laughing. Doris is wearing a low-cut black cocktail dress and high heels, her black hair piled on top of her head, glamorous and happy. She’s marrying a doctor!

It was a second marriage for both. Thomas met his first wife in the Philippines. She may already have been a nurse. When he got out of the army, they went to Memphis where he got his optometric training and afterwards, he brought her to Oklahoma and established an optometric practice in Antlers. His parents Sid and Oma Hawks farmed about forty miles away in the community of Bokchito. Ronald Patrick O’Brien Hawks was born in Durant on October 4, 1948. Pat, as we called him, attended school for at least two years in Antlers before the marriage broke up and his mother took him to Memphis and resumed her nursing career. In letters, she always claimed that she and Thomas were still married because the Catholic church didn’t recognize divorce.

I only knew Mary O’Brien Hawks from her signature in the novels she left behind, written with the authority of one who could not only afford hardcover books but had the sophistication to spend her money on fiction. If my people had disposable income, they didn’t spend it on books. Clothes, maybe. Mother dressed us beautifully.

The Tamarack Tree by Howard Breslin (1947) was the first adult novel I ever read. Thomas passed it along and suggested I not mention to Doris what it was about. There were some explicit love scenes, though nothing that would raise an eyebrow today. More shocking was a fight where the hero is pierced through the hand with the tines of a pitchfork. His lover knows the wound needs disinfecting and she makes a solution from tobacco, wraps a strip of fabric around a wire, and runs this swab through his hand. The image is with me still. I don’t know if tobacco is really a disinfectant.

Acquiring reading material started for me almost as soon as I could read. Nurse Nancy came with a little thermometer and some Band-Aids. I got my first Nancy Drew mystery for Christmas and discovered that girls at school had other titles we could trade. Like Abe Lincoln, my eyes scanned living room shelves for books I could borrow. If they had books at all, other than the Bible, it was Reader’s Digest Condensed Books and O. Henry prize winning short stories.

I was fascinated by a story called “Big Blonde” from 1929 that described the life of a woman who made her way in the world as a party girl. Men took her out and gave her “fifty for the powder room,” a concept that wasn’t explained to me until I visited Manhattan when I was nineteen and found that ladies rooms had an attendant, a black lady who went in after you and made sure the toilet was flushed. There was a saucer for you to leave her a tip. At the time, I was myself getting fifty for the powder room, and like Big Blonde earning those fifties being a fun date. I didn’t recognize the author’s name back then, Dorothy Parker, the Algonquin round table wit who said about Katherine Hepburn’s acting, “Her emotions ran the gamut from A to B.”

I loved stories written from a woman’s point of view. Annie Jordan: A Novel of Seattle by Mary B. Post (1948), Hear This Woman by Ben & Ann Pinchot (1959), The Egg and I by Betty MacDonald (1945), Good Morning, Young Lady by Ardyth Kennelly (1953), The Dark Island by Vita Sackville-West (1936), Marion Alive by Vicki Baum (1941). I was reading these novels years, even decades after they were bestsellers.

Kitty Foyle (1940) was a favorite, but certain details didn’t ring true. Kitty’s dialogue, for instance, was like no woman I had ever heard. Nor did I think a woman who sold perfume for a living would have so little in her medicine chest. Yet, when her lover Wyn looks in the cabinet, he notes approvingly that she only keeps a box of baking soda and her signature fragrance. Maybe that’s all that Christopher Morley had in his medicine cabinet, but Kitty Foyle’s would have been stuffed with cosmetics, especially bright red lipstick. After writing five novels from the perspective of arson investigator John Bolt, I know how hard it is to imagine the thought processes and speech patterns of the opposite sex.

Betty and I were excited to acquire a brother but as it turned out, I didn’t like Ronald Patrick Hawks. Skip ahead ten years and I’m sitting by an apartment complex pool in Pasadena, Texas with another young mother, watching our kids repeatedly dive, chug through the water, climb out, run to the end of the diving board and do it again. A man comes along the sidewalk and knocks at my door. It’s Ronald Patrick Hawks and he glances my way but I pretend I don’t recognize him. My neighbor drawls, “I guess there’s some reason you’re not answering your door.”

*****

My father Milford Mack Glass (1925-1999) was born in Vernon, Texas, the youngest of eleven children. His parents, Henry Franklin Glass (1879-1952) and Flora Lavona Price (1885-1940) were also Texans, from Hunt and Montague Counties respectively (pronounced Mon-tage by Texans). Mother’s people became landowners, which anchored them to a specific geographic area, but the Glasses were subject to the vagaries of landlords, weather, economic conditions, and Frank’s itchy foot. Half of Daddy’s siblings were born in Pushmataha County Oklahoma where Frank’s parents farmed near Rattan. The others were born in Hunt, Wise, Wilbarger, or Montague County Texas. Whichever side of the state line they were born, none of Frank and Flora’s children hailed further than fifty miles from the Red River.

Firstborn Lola (1901-1914) died of influenza at the age of twelve. (Spanish flu was first reported in Kansas in 1918.) Two years later a boy was born in Rattan but died before he could be named. Third child Oma May (1905–1944) grew to adulthood and married Robert Joe Wilkinson in 1926. As a child Oma suffered strep throat that turned into rheumatic fever and damaged her heart. Today, antibiotics prevent the spread of streptococcus bacteria to the heart and we no longer hear of young people dying of congestive heart failure. Oma was unable to have children and at the age of 29 she and Robert adopted a boy they named Robert Kern Wilkinson, born in 1934 and at this writing 87 years old.

When Daddy’s ship was in port in Hawaii, he looked up his brother Herman, working as an orderly in an army hospital. The brothers were together when they learned of Oma’s death on November 16, 1944. I wasn’t born yet, but I remember how Robert Kern was always greeted at the Glass family reunion with tears and hugs. The sight of him evoked the memory of the eldest sister whose death robbed Robert Kern of his second mother before the age of ten.

Flora Glass was 34 when her ninth child, Herron Hack, was born in 1919, at which time she would’ve had five children under the age of ten. When her eleventh child, my father, was born in 1925, she was 40 years old. Omah was about to be married, Dessie just turned seventeen, Leonard sixteen, and their sister Nelie thirteen. Even so, the new baby was welcomed and adored. At the Glass family reunion, I basked in the reflected glow of the “baby of the family” and everybody’s favorite.

Dec. 5, 1990

Hello Birthday Brother. You will probably never know how proud we brothers and sisters were of you (and still are). You were like a new toy to us only we could love and spoil you (which we did). I remember when Momma decided she would have to put you on a bottle. She thought she had failed you. She cried. We thought you and your bottle were so cute. We all loved you so much (and still do). Then as you grew older, age 3 or 4 you would get into bed with Nelie and I and want us to tell you a story. You knew each one by memory and if we missed one word you would make us go back and start over again. We spoiled you so much but I’m glad for all those precious memories. God Bless you on your birthday and every day. Love, Dessie [Dessie Ola Porter 1908-1996]

Dessie and Nelie helped raise the younger ones, Mack 1, Troy 4, Hack 6, Herman 8. Eldest by default, Oma was the first to marry. Then in 1932, Nelie Myrtle [1912-1995] married Willie Lee Williams and gave the family its first grandchild, my oldest cousin Bobby Lee Williams, born in September 1933. Two months later, on November 15, Dessie, now 25, married Raymond McAlister, a neighbor ten years her senior. The oldest brother Leonard also got married that month, November 28, to Opal White. Their marriage ended when I was a child, but their children were the cousins I grew up with in Arizona, Gladys, Gerald, and Glenn Glass.

Dessie and Raymond were married only ten months when he was killed by lightning while the family was scrambling to get in the cellar during a north Texas thunderstorm, one of the many family stories woven into my novel Oklahoma Air. Dessie was holding onto Raymond and was also injured but Leonard managed to carry her to safety. Three years later, Dessie remarried, this time a man six years younger. She and Grady McKinney Porter wasted no time having their only child LaNita J. (There are no documents showing that “J” was anything more than an initial.) My cousin LaNita J grew up, but her kidneys did not. She endured years of dialysis before receiving a kidney transplant. “I can pee!” she exulted to Uncle Hack hours after the successful operation.

Price Henry Glass [1914-2003] was next of the Glass children to marry, to Ruth Cox in July 1934. My father was six at the time and always enjoyed teasing this sister-in-law, which she took in the spirit it was given rather than backhanding him. Aunt Ruth was the genealogist in the family who compiled a family tree of the children of Frank and Flora Glass without the benefit of computer or the internet.

Herman Caylor Glass [1917-1990] married Clara Camp in 1941. Their two sons David Wayne and Roy Don were the same age as me and Betty and when we spent the night with them in Rattan, we four little kids were tucked into the same bed. My farmer uncles Herman and Hack raised peanuts and cotton, north and south of the Red River, raising their families in houses that had never known a coat of paint. I picked cotton for one day, laboring alongside my cousins and learning firsthand what it takes to fill a cotton sack, one of the many experiences that made me determined to get an education.

In September 1940, Herron Hack Glass [1919-2010] married Helen Dorothy Standley, and the following month his brother Troy Mancell Glass [1921-1976] married her sister Hazel Frances Standley. Eight of the Glass siblings lived to organize and attend the Glass family reunion.

Family gathers from 8 states for 42nd Glass Reunion

The Oaks Shores Club House saw many hugs and much excitement this weekend as relatives of the Glass family came together for their 42nd annual family reunion. This year approximately 75 relatives were drawn from over 20 different cities in eight states extending from Louisiana to Washington. The reunion was attended primarily by the descendants of Frank and Flora (Price) Glass… There was representation from all but one of these nine Glass children. Fourteen of the remaining 19 grandchildren were able to attend bringing many of their children and grandchildren with them. [unattributed news clipping, probably The Nocona News, 1993]

The reunion was held on Uncle Leonard’s birthday in September. Aunt Dessie was a year older, but her birthday was in January, too cold for an event where people spilled out of ramshackle houses onto porches and out under shade trees. Dessie and Hack took turns hosting the reunion, at either Lake Bridgeport or Nocona. My twenty-three first cousins and I learned to dog-paddle in the Red River with a sturdy barricade of aunts keeping us from being swept away by the current. Whatever cut-offs or swimsuits we wore was ruined by the muddy red water. The men and older boys set out trotlines overnight to catch the fish we would be eating the next day.

In later years the Glass Reunion moved to less primitive quarters, the clubhouse at Lake Nocona. The two days were spent catching up with family you hadn’t seen for a year, interrupted by enormous meals. Sleeping arrangements were haphazard, as there were never enough beds and a Glass rarely shelled out for a hotel room. At some point the older generation would be urged to pose for pictures. Who knew which of them would not show up next year? Daddy and his brothers and sisters would line up in lawn chairs while their children, grandchildren, nieces, and nephews snapped away like paparazzi.

Daddy’s brothers worked with the dirt as farmers, dozer men, landscapers. Sisters and wives worked with food as school cafeteria cooks and homemakers. Several of my aunts were famous for their cooking. Several of my aunts were enormous.

The three oldest of Daddy’s siblings died before I was born. Uncle Troy, only four years older than Daddy, was next to go, felled by a stroke at Wednesday night prayer meeting. Aunt Hazel sold the house in Lubbock and moved him to Nocona where her sister Helen, married to his brother Hack, had already moved. After Uncle Leonard retired in California, he and Betty bought a house on the shores of Lake Nocona. Just as when they were kids, the Glasses wanted to live close to each other. The things they had gone through together—poverty, the death of siblings, the Depression, World War II—knitted them together, while my generation, we boomers, who had things so easy, have barely kept in touch.

Troy lived with his disability for a few years and died in 1976 at the age of 55. Uncle Hack was the longest lived, to the ripe old age of 91. He died in 2010, surviving ten years beyond the death of my father, baby of the family.

When we were kids, I was afraid of Uncle Hack. He had one milky eye, and there was that incident that happened in Uncle Troy’s front yard. He and Hazel had not yet bought the new house over on Avenue A. In Lubbock, the Glasses and Standleys were clustered along an unpaved road east of the city surrounded by cotton fields. One day a stray dog came up and we kids begged to keep him. Uncle Hack sent us inside, took his rifle out, and shot the dog. Only as an adult could I appreciate that he was protecting us. In those days you couldn’t be sure a stray animal wasn’t the carrier of a disease that could kill your children.

Henry Franklin’s mother Arminda Lynch Glass (1857-1938) was born in Hunt County Texas in the northeast part of the state roughly between Paris and Dallas. Like the Glasses, the Lynches came from Kentucky, though it’s not clear if the Glasses of Barren County knew the Lynches of Wayne County before they all fetched up in Texas. Barker Taylor Glass and Arminda Lynch were married June 6, 1875. She was 18, he was 23. Their first child William Barker Glass was born the following year and settled in Spur in the panhandle. I never knew him, but his children were Daddy’s cousins Hester and Faye, regulars at the Glass Reunion.

Barker and Arminda’s second son was my grandfather Henry Franklin Glass. There were nine more children, eleven being the number of births a healthy woman at the end of the 19th century could expect to achieve in her 22 years of fecundity. The youngest Glass, my uncle Doc, was born the year Queen Victoria died, in 1901. Amazingly, his mother was 45 years old at the time. Olin Barker Glass, “Doc” in the family, married Elizabeth Benefield, my Aunt Bee. They had two children, Billy Lee and Linda Oline, who was two months older than me and had the same first and last name. First National Bank in Antlers once mixed up our accounts. I knew at once there had been a mistake because that Linda Glass had a lot more money than I did. She and Billy earned money working in their father’s fields. Doc and Bee’s house north of Rattan was a work in progress, set seemingly at the end of the world. When we went to see them, Daddy would stop the car in the middle of Rock Creek and we would all get out and wash the car.

My great-grandmother Arminda Lynch Glass lived to be 81 and is buried in one of the two dozen Glass and Price graves in Rattan Cemetery. Barker is buried out in Stephens County Oklahoma, keeping company with two of their children, Allen and Edward. Those grave markers are chunks of red sandstone scratched with their name and little else. Barker’s reads “B T GLASS.”

Barker Taylor Glass (1852-1921), my great-grandfather, was born in Barren County Kentucky, named apparently for his mother’s father Barker Taylor Anderson. There’s very little information about his mother Mary “Polly” Anderson Glass, my great-great-grandmother, other than that she married William Henry Glass (1829-1864) on January 1, 1850, and ten months later bore a girl, Malinda Jane, whom they called “Cis,” short probably for “Sister.” Confusingly, William had a sister named Mary Polly Glass.

The Glass family next appears in the Hunt County Texas Census of 1860 in the home of Henry and Elizabeth Arnold, although without Mary. I can find no record of her death, but I’m guessing that her death sent William and their two children to Texas to live with relatives or former neighbors from Kentucky. The 1860 Census is also the last mention of William, although I know of his death from the genealogical records of his parents Ben and Susannah Franklin Glass. He would have been 35, Malinda Jane fourteen, and Barker twelve at the time. Malinda Jane Glass Morris lived in Hunt County for the rest of her life, dying in 1921 after adding sixteen children to the family tree, including one set of twins. Barker also died in 1921, he at the age of 69.

Like most people, I didn’t get interested in family history until late in life and believed that the Civil War stood as an impenetrable barrier to the past. Over and over I heard a theme of twin brothers traveling alone on the train from Glasgow, Kentucky to live with relatives in Texas after their parents were killed in the war. Four generations are ample time for family history to become legend.

Glasgow, county seat of Barren County Kentucky, named by its founder for his home in Scotland, is near Mammoth Caves on the Natchez Trace. The residents were Confederate in sympathy but after a brief skirmish early in the war, the Union built a garrison there and the area saw no further action. There were, however, any number of other ways to die than becoming a casualty of war. Mary Polly Anderson Glass may have fallen to contagion.

In September 1853 the city was struck by its greatest disaster, Asiatic cholera, which threatened to wipe out the populace. The disease was brought to Glasgow by a traveling circus and the big spring, main water source for the city soon became polluted, infecting members of almost every family in town. Some fled, but many stayed to nurse the sick and bury the dead until the disease had run its course.—City of Glasgow website

My father was a sentimental man, easily moved to tears, especially when it came to family. One night when Betty and I were little, I woke up to find Daddy sitting on the edge of the bed sobbing. I said, “What’s the matter, Daddy?” He said he was missing his momma. Flora Price Glass had been dead for fifteen years yet his grief was fresh. My grandmother was fifteen when she got married and she spent half of her adult life pregnant. She raised her children in rundown farmhouses without electricity or running water. When I read Robert Caro’s description of the lives of Hill Country women before electrification, I thought of her and my other Oklahoma and Texas grandmothers. The chapter called “The Sad Irons” is in the first volume of Lyndon Johnson’s biography. Stephen Harrigan wrote that it’s “the most brilliant single passage of prose ever written about Texas.” [April 1990 issue of Texas Monthly]

Daddy’s two sisters, his older brothers, and the girls they married, tried to keep him in school, but Milford Mack ditched as often as he could and ended his formal education after the fifth grade. Daddy could read and write, could even compose a decent letter, but he never got the hang of punctuation and when he was done writing, dotted his letter with commas and periods, evenly if not grammatically.

A man whose entire collection of footwear consisted of two pairs of Sanders handmade Western boots, monotone but covered in fancy stitching, my daddy loved the Old West, its myths, its music, its literature. Sitting in his hoist shack waiting to move miners up and down the shaft, he read Zane Grey and Louis L’Amour. When television came along, he became an ardent fan of Gunsmoke and Bonanza. Chester, Miss Kitty, and Hoss Cartwright were real people to Daddy. Before the days of DVD’s, he was frustrated there were reruns of the 635 episodes of Gunsmoke that he kept missing.

Uncle Hack and Aunt Dessie had the longest memories, but neither of them could tell me where the Glass name came from, unless it was somehow related to “Glasgow,” they supposed. Here’s where the name came from: Barker Taylor Glass got the name from his father William Henry Glass, whose father was Benjamin Glass [1790-1853]. Ben got the name from Samuel Glass [1755-1815], who got it from his father Robert David Glass [1716-1797]. Robert Glass entered Virginia Colony nearly thirty years before the formation of Frederick County, Virginia’s northernmost county.

The Glass name crossed the Atlantic with Samuel Fielding Glass [1690-1767] of Seapatrick, County Down, Northern Ireland. He and his wife Mary Gamble Glass brought six children with them to Virginia Colony. You will recall that Jamestown Colony, settled on the banks of Virginia’s James River in 1607, was the first permanent English settlement in North America. For a hundred-and-sixty years, people were Virginians before they were Americans.

Samuel Glass built Greenwood Homestead in 1738 and Old Mill in 1740. The caption on a photo of this handsome structure reads that it was the only one of its kind in the county.

Samuel Glass and Mary Gamble his wife, who came in their old age, from Ban Bridge, County Down, Ireland, and were among the early settlers, taking their abode on the Opecquon in 1736. His wife often spoke of ‘her two fair brothers that perished in the siege of Derry.’ Mr. Glass lived like a patriarch with his descendants. Devout in spirit, and of good report in religion, in the absence of the regular pastor, he visited the sick, to counsel and instruct and pray. His grandchildren used to relate in their old age, by way of contrast, circumstances showing the strict observance by families—Mr. Glass, in the midst of wild lands to be purchased at a low rate, thought sixteen hundred acres enough for himself and children. [From Shenandoah Valley Pioneers and Their Descendants, by T. K. Cartmell, published in 1908, as taken from Sketches of Virginia, by Dr. William H. Foote, published in 1855]

The plinth over Samuel’s grave reads: Emigrants from Banbridge County Down Ireland. A.D. 1736. Their children: John, Eliza, Sarah, David, Robert, Joseph were all born in Ireland and came with them. Their decendents are to be found in Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, Ohio, Indiana. And I might add Texas, Oklahoma, and many other states as well. Samuel’s father was John Glass II, son of John Glass who lived in the 1600’s.

I would so love to have been able to tell my family where our name comes from.

The Glasses were not my only ancestors to cross the Atlantic and settle in Virginia Colony in the 1600’s. Arminda Lynch’s family came over from Leicestershire, England. Her mother’s maiden name was Abney but changed to Abner in the new country (Lucinda Abner Lynch, 2 Apr 1829 – 17 Oct 1888).

Dannett, our ‘Gateway Ancestor of Virginia,’ came to America on the Frigate/ Barque/Fluyt ‘Josiah’ under Captain Sharpe about 1679 sailing in the company of his brother Paul.—Raymond Robert Abney

I was six years old when my grandfather Henry Franklin Glass died. He outlived Flora by eighteen years and remarried. His second wife Nettie McAtee was a native of Montgomery, Maryland, born in 1878, widow of Dr. Ebenezer Reynolds. Nettie was 38 when she married Eben and they had no children. He was 58 and had one daughter, Erie Labor Collins. In a photo taken when I was about two, my grandfather, holding me in his lap, poses next to Nettie in front of the little house she owned below Standpipe Hill in Antlers. I imagine those twelve years Frank lived in that house were the longest he ever stayed in one place.

Betty and I were fascinated with Nettie’s parakeet Peetie and the fact that Nettie was profoundly deaf and wore a hearing aid connected by a wire to a box she kept inside her blouse. I spent the summer of 1960 helping care for Nettie so her nurse could go home for a few hours’ sleep every day. My duties consisted of helping the bedridden patient with the bedpan and heating some soup for her lunch. Mostly Nettie slept and I sat in the living room working my way through the musty novels in her bookcase. When Nettie died the following April, she was buried next to her first husband in Ethel Cemetery next to the school yard where we played as children.

*****

In one of my parents’ many separations, Mother took us to live in a little cottage down the road from my grandparents. The lane continued on past our house deep into the woods where three strange women lived. The oldest and youngest cared for a middle-aged woman they said had been left tied to a drainpipe till she went out of her mind from the continual drip of water on her head. My mother identified with the beautiful granddaughter Maranda and prayed that a knight in shining armor would ride up and carry her away, even though that escape route had not worked out for her. Despite my mother’s disappointment with my father, and later with a succession of stepfathers, she never gave up hoping that Betty and I would find husbands we could rely on to take care of us.

The cottage at the end of the lane had electricity but no running water. Mother cooked on propane and heated water for our baths. My first cooking lesson was on that stove, a pan of cornbread that made my sister lose another tooth. Grandpa sent us a young cow so we would have fresh milk. Milking time was always an adventure. Betty and I would clamber up on the fence to watch the show. As soon as Mother appeared with the milk pail and a can of feed, the feisty young cow would race her to the shed. Mother would leg it down the path, fling the feed in the trough, and leap up on the fence to avoid the deadly black horns.

Our mother was afraid of everything and it must have taken a lot of courage to set off across the desert with two little girls and just enough money to get them to Oklahoma. Or head into a pasture to milk an untamed heifer. Or live in an unheated cottage at the edge of the Kiamichi wilderness. That winter Betty and I both came down with measles and Mother set up cots in the living room so we would be closer to the wood stove. During the night, the fire went out and she had to go outside and bring in more wood. She got the fire roaring again and Betty sat up in her cot and vomited. Seeing my sister be sick, I threw up too and Mother sat down on the end of the cot and wailed.

In the spring we packed up to go back to Daddy. Mother didn’t have any boxes, so she told Betty and me to start bringing stuff out to her. I carried out the salt and pepper and cinnamon, which got packed first. It was our parents’ last attempt at reconciliation. They were divorced in 1956 and Mother never had to see Arizona again. My sister remembers going with them to Globe to file the divorce papers. She remembers that they seemed really pleased with themselves.

*****

Mother bought my grandparents a television set. An antenna mounted on a pole brought in two stations, Ada and Paris, Texas. To adjust the picture, you had to go out in the yard and twist the pole around while somebody yelled from the window whether that improved things or not. Betty and I were instant converts and Mother would make us rest our eyes during commercials. On Friday night the whole family, except for Uncle Bud, gathered to watch Circus Boy and Rin Tin Tin. Grandpa liked boxing. Uncle Bud thought TV was evil. He would pace nervously in the background, nodding his head and muttering. He changed his tune when preachers began televising revivals, our own Oral Roberts from Tulsa, and Billy Graham from Tennessee. Uncle Bud would hold his Bible in one hand and lay his other on the set and close his eyes.

George Alva Lee Perry, Jr. (1920-1995), his parent’s only surviving male child, suffered from grand mal seizures. His older sister Carrie Ecil also had seizures but told my sister they only started after she had a car wreck as an adult. When Ecil brought her baby girls into the Perry household, my grandparents committed Junior to the state hospital for the insane in Vinita, Oklahoma. They must have struggled with the decision for Grandpa returned to check on him and found they had whipped Junior with a rubber hose and he packed up the boy and brought him home. Uncle Bud never did mistreat the babies, though he could get awfully worked up over balky farm animals.

Autism had not been defined or named yet but it’s likely Uncle Bud would get that label today. He might also earn the sobriquet “savant.” Although he never attended school, he could read and write and do sums faster than the adding machines of his day. Phenobarbital, coming on the market in the ‘40’s, ended his seizures. He had a sweet disposition and sought out company. After they sold the farm and moved into town, he met his social needs with a daily walk-about. He had never been trusted to drive (or shave himself) and Antlers merchants and townspeople became accustomed to seeing him trudging along the streets with his many home-made knapsacks. The kids called him Gopher Man.

Uncle Bud considered gophers vermin and did his best to eliminate them from his corner of Oklahoma. He could study the terrain and figure where to set his trap along their runs. Thanks to his machine-like memory, he could recite their number, weight, length, and whether or not they were lactating females. He played hymns on the harmonica and composed songs and poetry he copied out in pencil on reused grocery bags and envelopes. He studied the Bible and could recite long passages. It seemed to me his interest was more about the peculiarities of language than the theology. For example, he found the longest words, the shortest verses, how many times a certain name appeared, and many other statistics that didn’t make their way into my own long-term memory.

Patterns fascinated him. He recited the alphabet backward and forward at the same time. He memorized the grocery list, knew telephone numbers, and acted as a human calculator. He seemed to never forget anything. For all his brilliance, he was modest, usually starting sentences If I’m not mistaken….

When telephone service became available, my great-grandparents hooked up to the party-line. You knew from the number and duration of rings who was getting a call. Grandpa regarded this instrument as a public forum and evenings sat out in the hall where the telephone was located and listened in. Margie Mills, married to my father’s cousin A.V., was our telephone operator. Mother could pick up the phone and say, “Margie, will you get me Dr. Haddox?” Or we might ask her for the correct time. When operators lost their jobs to rotary phones, our number, 333, changed to Cypress 8-3333.

There was no plumbing in the Perry house. A bucket of water and an enameled dipper from which everyone drank sat on a shelf just inside the backdoor alongside an enamel basin to wash your hands. All liquids were flung out the back door which brought the chickens running to look for scraps. There was a deep well in the backyard, essentially a pipe in the earth. To fetch water, you lowered a tube-shaped bucket that just fit the opening by way of a chain that ran through a pulley overhead. After drawing the bucket up, you released the water by pulling a plunger at the top of the tube.

Water was also collected in a big rock cistern from rainwater that sluiced off the roof. Grandma used that water on the houseplants that crowded the screened in porch. One day someone left the wooden lid off the cistern and an adventurous hen fell in. We all watched as Grandpa lowered Uncle Bud in the bucket to fish her out. Her protests on the way up nearly got her neck wrung.

Grandma had a green thumb. Plants both ornamental and edible thrived under her care. In the summertime the front yard was filled with blooms. Honeysuckle draped the fences. She was especially proud of her snowball bush at the corner of the house. Grandma tended a garden out behind the chicken shed and we ate fresh vegetables in the summer and canned in the winter. Uncle Bud brought home blackberries, plums, small sour apples, a green grape called muscadine, persimmons, poke salad, hickory nuts, black walnuts, and pecans. Grandma made pies, jams, jellies, and butters. She made biscuits and cornbread, milked the cows and churned the butter. She made cookies I’m still trying to duplicate. She stored Mason jars of home-grown produce in the backyard cellar. Grandpa came home from the woods with squirrel and rabbit the dogs scared up for him to shoot. We ate well.

A great iron pot in the backyard, once used in the processing of pork, was now used to boil water for the laundry. Washday was a mighty production. Beds were stripped, towels and washcloths gathered up, plus every stitch of underwear and clothing we could spare. Dirty laundry was fed through lye soap water in the order of its relative cleanliness. You could rotate the wringer around to serve each of the four zinc tubs and little girls learned to keep their fingers and hair clear. Mother hung wet laundry on wires strung across the backyard, and when gathered in, the clothes were stiff enough to stand up by themselves.

Mother’s girlhood stories featured snakes, angels, and miraculous events. She warned us to watch out for mountain boomers (frilled lizards) that ran toward you rather than from you, panthers, and Roy Jackson’s brahma bulls. One Christmas we went into the woods to look for a perfectly shaped tree and found just the right one on the other side of a barbed wire fence. Uncle Bud climbed over with the saw and began cutting the tree. Suddenly we heard a low thundering roar that got louder and a herd of pale hump-backed beasts emerged from the woods. We had probably chosen the very spot where Mr. Jackson came to feed his cattle. We screamed at Uncle Bud to leave the tree, but he just sawed faster, determined to get what he came for. At the last possible instant, he flung the tree over the fence and climbed to safety.

One time my mother, as impatient as she was impetuous, struck out across the fields to attend a party at a neighbor’s house, leaving Grandma and her little sister Blue to follow with the food. Nearing her destination, Doris found her way blocked by a big snake curled up on the footpath. She was deathly afraid of snakes and didn’t want the others to come along in the dark and step on it. She climbed a fence and started hollering a warning. Aunt Helen tells the story somewhat differently. She and Grandma came along and rescued Doris from a snake that was long gone.

Doris and Blue were in high school when Antlers was hit by a great tornado. It happened on April 13, 1945, the day after Franklin D. Roosevelt died.

More than 340 people, or 10% of the town, were hospitalized, some of them taken as far away as McAlester and Paris, TX. Sixty-nine people died. Local authorities were overwhelmed and volunteers came from all over the state. Bodies were transported to funeral homes up to a hundred miles away. Fifteen hundred people were suddenly homeless. The Red Cross handed out more than 4,000 meals in the first four days after the tornado, and churches that weren’t destroyed set up cots and people who weren’t touched by the storm took their neighbors in. Others found shelter in nearby communities. Twelve children from Antlers were taken to the Oklahoma Hospital for Crippled Children.

An Associated Press reporter said that survivors “appeared dazed” and several “stood on street corners all night talking about the disaster.”

The Antlers grade school was spared and served as the community hub. Many downtown buildings were leveled. At one intersection, all four corner businesses disappeared, leaving only their foundations. Debris from Antlers was found more than ten miles away and human bodies as well as livestock were distributed across several acres.

While Antlers was the hardest hit, it was not the only Oklahoma area that got walloped. Eleven were killed in Muskogee, four in Oklahoma City, three in Hulbert, and nine more in other communities. Boggy Depot, a tiny speck of a community on Indian Territory about 45 miles west of Antlers that consisted of only 10-15 homes and a few businesses, was completely wiped off the map. Today it’s a ghost town on State Park land.

The same storm system killed twenty in Arkansas and five in Missouri. Two weeks later a tornado touched down in Pryor, northeast of Tulsa, and killed 52 people.—Coryell Roofing, 2020

The sisters knew something bad had happened when checks from the bank miles away fluttered down from the sky. Aunt Hermione was married by now and living in town. She described picking her way through the rubble, seeing block after block of destroyed homes and businesses. There used to be a Catholic convent in Antlers. It was never rebuilt. Nor did Antlers ever fully recover. The population in 1940 was 3,254. The Census of 1950 recorded 800 fewer residents, and when I was in high school in the 1960s, the population was 2,300 where it’s been ever since.